The End of an Era

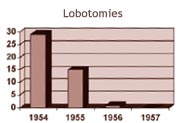

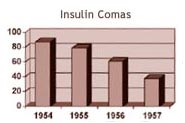

The following charts show the rapid decline in use of certain medical treatments between 1954 and 1957, in favour of the new medications:

|

|

|

Source: Adapted from Douglas Hospital 1957 Annual Report

Between 1950 and 1956, 140 lobotomies were conducted in Perry Pavilion's surgical room, located on the second floor. The operation involved cutting nerve fibres between two areas of the brain (the frontal lobe and the thalamus). It was thought that an interruption in the flow of information between these two areas could reduce severe obsessive anxiety and depression. Although there were a few successes, the procedure tended to cause irreversible damage to patients' brains. In some patients, serious personality

disorders emerged. This technique, along with insulin coma treatments, rapidly declined between 1954 and 1957, as superior treatments were discovered.

No Guidelines Required

In contrast to today’s strict research environment, Heinz Lehmann and his Douglas colleagues had no formal research guidelines. They continued to test twelve or so drugs over the next few years with no written protocol, no stated criteria for selecting the patients, no placebo or other controls, no government permission, and no informed consent from the patients or their families (who happened to usually be

quite happy about the treatment), and all without financial assistance or government grants. From 1961 to 1977, Heinz Lehmann's success had become so renowned, he received grants from a variety of organizations totalling one million dollars to continue his research. Together with a Douglas colleague,

Thomas Ban, MD, he tested a number of antipsychotic medications—some of which were highly effective and are still used today.

Research Centre: Founders Tried Drugs on Themselves First Research Centre: Founders Tried Drugs on Themselves First

And finally, in 1980, the Douglas Research Centre was born. We owe its creation to psychiatrists N.P. Vasavan Nair, MD, and Samarthji Lal, MD, who in 1980 began a competitive research program with a budget of $200,000. Recalls N.P. Vasavan Nair, "Money and equipment were in short supply— and so were subjects for clinical studies. Heinz Lehmann had been a great experimenter on himself. In those days, we followed his example and tried the drugs on ourselves before giving them to our patients." In 1980, the Centre opened the first brain bank in Canada and in 1981, became a World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Research and Training in Mental Health.

Drugs For Mind Like 'Cast On Broken Leg’

Article from The Gazette – January 3, 1956

An outstanding medical development of 1955, and one in which Montreal doctors played a leading part, was the broadening of the scope of newly discovered "medicines for the mind". First used solely for the treatment of patients in mental hospitals, these drugs on which pioneer research was done at Verdun Protestant Hospital and the Allan Memorial Institute here, began to be widely used during 1955 for the reduction of excitement, tension and anxiety in situations of emergency and even in routine, stressful situations of ordinary life. The term “mental aspirin” began to be applied to the drugs and it was suggested that the psychiatrists had at last a simple treatment that would be as important and effective in their file as penicillin had proved to be in the conquering of purely physical ills.

Dr. Heinz Lehmann of Verdun Protestant Hospital and one of the first doctors in North America to use the new drugs clinically, returned from an international meeting in Paris to report that one of the drugs, chlorpromazine, had been used by French military psychiatrists to enable soldiers to face stress and conquer fear during the fighting in North Africa. Dr. H. Azima of the Allan Memorial Institute, also a pioneer in the use of the drugs for which he used the term “psycholeptic” (psychological tension-reducing) substances, has prepared a

paper in view to bringing general practitioners up to date on the subject. He says: "There has been recent evidence indicating that in states of social disorderliness, panic and agitation, administration of psycholeptic substances, either to a leader or members of the group… will increase the managing and controlling power of the leader and the members. It is conceivable that, particularly in small communities, outbursts of what can be called mass agitation and hysteria may be controlled by administration of these drugs.”

Other doctors have suggested that the drugs might eventually be used routinely in such situations as that of a patient facing a serious operation, a judge presiding over an important trial, an actor with “first night jitters” or a salesman tackling a “tough” prospect. At this point, the medical men closest to the situation sound a warning. The drugs, Dr Azima told the general practitioners, are “indications of a new era in psychiatric and psychosomatic therapy”. But, he added, “they are far from constituting the penicillin period of psychiatry…we should not let our enthusiasm accelerate unduly the vehicle of our scientific accuracy.” The drugs do not, he said, cure mental illness or affect the root cause of anxiety and tension.

Their main use is in enabling a person to carry on normally despite a basic disability and in calming an excited patient to a point where the psychiatrist can “reach” him.

Dr. Lehmann describes the drugs as "something like a cast on a broken leg," The cast has no direct action on the injury, but it does enable natural healing processes to go forward at top speed and efficiency. A point on which everyone is in agreement is that the discovery of the new drugs about thre e years ago was one of the greatest achievements of the 20th century and that the scope of their usefulness is broad and expanding.

|